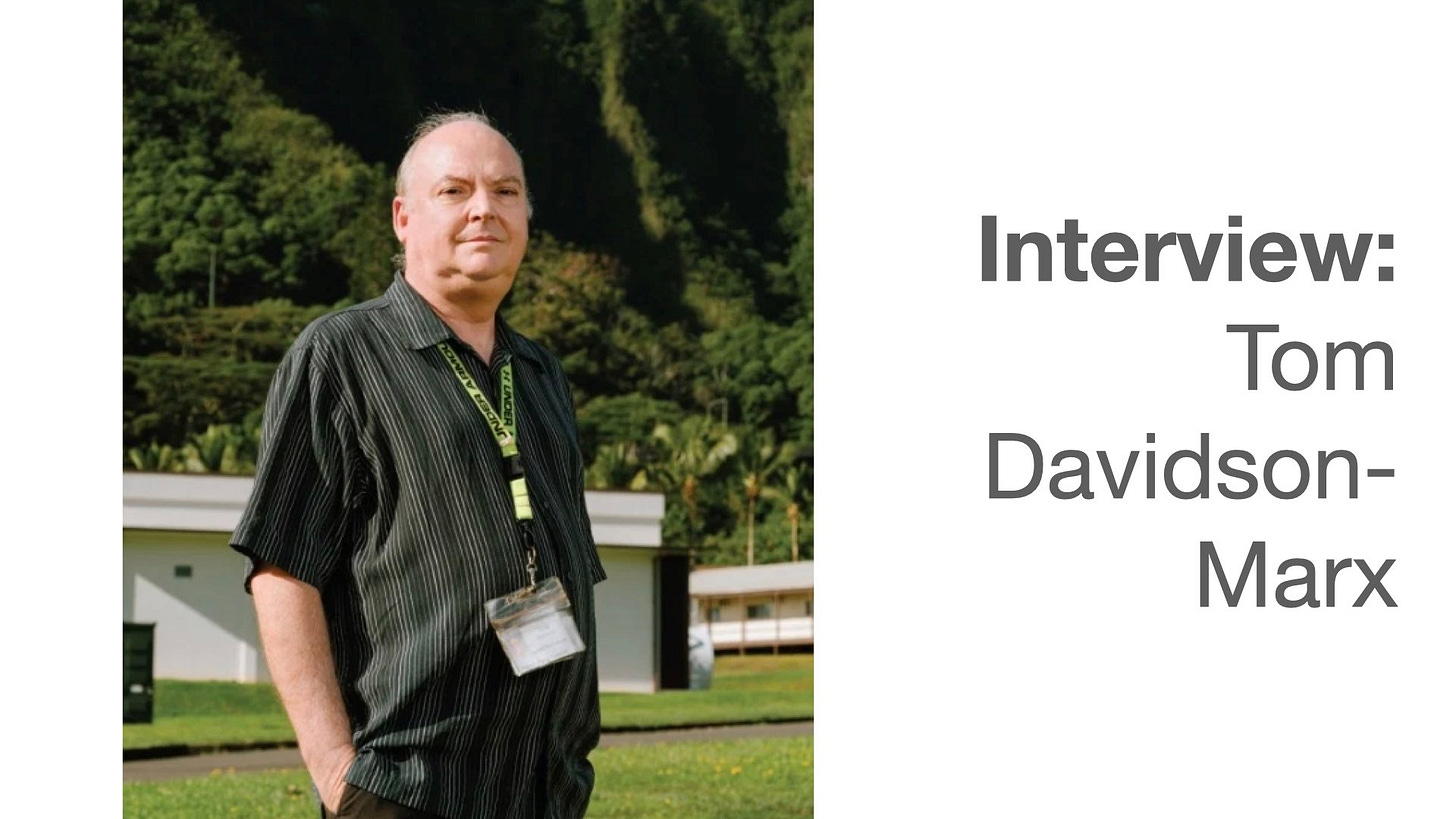

Tom Davidson-Marx is the co-founder of Aloha Sangha, a secular meditation group based out of Honolulu, Hawaii.

In this conversation he shares his journey through Buddhism, from his first meditation retreat to becoming a monk in Sri Lanka, and his later experiences balancing spirituality with everyday life. He shares profound insights on meditation practices from intensive practice, the challenges faced, and the benefits of integrating spiritual teachings into a balanced life.

Tom also touches on his eclectic approach to teaching meditation and the establishment of Aloha Sangha, a non-traditional meditation group focused on love and compassion. This conversation provides a deep dive into the practical and philosophical aspects of Buddhism for lay and experienced individuals.

Connect with Tom @ AlohaSangha.com

Time Stamps:

00:31 Introduction and Retirement Reflections

01:15 First Meditation Retreat Experience

06:43 Life Journey and Early Influences

08:08 Discovering Buddhism and On His First 10-Day Retreat

10:35 Becoming a Monk in Sri Lanka

18:24 Deep Dive into Meditation Practices

24:55 The Bliss and Challenges of Meditation

33:32 The Ultimate Goal: Nirvana and Liberation

42:43 Steps to Achieve Bliss in Meditation

43:11 Analyzing the Self: Deconstructing the Notion of Self

44:10 Meditation for Beginners: Awareness and Intention

44:51 The Evolution of Meditation Practices

46:32 The Dark Night of the Soul: Understanding and Coping

51:08 Grounding Techniques in Meditation

01:06:36 The Importance of Balance in Life and Meditation

01:13:29 Future Plans and Non Dual Spiritual Reflections

Post Script Notes from Tom:

Now, 45 years after my first 10 day retreat, the words from T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding,” feel so true:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

What’s changed for me? This continuous stream of present moments unfolding right now is already transcendental, if you will, and has always been so. If this is so, do you even have to practice meditation? That’s an open question, and a good one to ask yourself as you begin this most amazing journey.

Quotes of Interest from Interview:

On The Purpose

So the whole point of Buddhism is to become a better person such that you actually give back and are compassionate and help other people. That's the goal.

On Meditation

Meditation is something that needs to be done with a lot of care and a lot of understanding of what is actually happening….you can't just like ignore everything and think meditation is going to answer all your questions, all that, you know, be the answer to all your problems or concerns or whatever.

On Mental Colonization

you start to notice how much mental energy was bound up with, fruitless ruminations over the past and equally fruitless preoccupations with the future…. the notion starts to form that what we're taking as the feedback loop from our mind , what we're evaluating and what we're judging and what we're comparing, is only a very small part of our of our mind, and it's the part, unfortunately, that has colonized the rest of it.

On the Non-Dual

Noticing the non dual nature of that, and to me the non dual nature means I don't really have to go outside of my own personal experience to have profound experiences, because it's already profound right now, right here, right now, it's already done, like, we've already crossed the finish line, there's nothing, something that we think we need to do is extra.

AI Transcript (Apologies for the glitches)

Tom: Buddhism doesn't hold all the answers. It has a very nice path, but that doesn't mean you have to, like, do it hook, line and sinker. You can do the techniques, but you can also adapt it to your life and your own particular outlook on life , in whatever way it suits you.

Introduction and Retirement Reflections

Leafbox: Tom, good morning.

Tom: Hey, how's it going Robert?

Leafbox: Hey Tom, you look good. Hey, so, congratulations on your retirement, how does that feel?

Tom: Well, it's been really good because I, the first day of my retirement was spent on the first day of a 30 day intensive meditation retreat which was challenging.

It was, yeah, it was there's an expression like you bite off more than you can chew or something like that. It was definitely definitely, wait, am I running over here? You asked a question and I just went off on how my retreat was, but

Leafbox: yeah. No, I think we can start.

Why don't we just start, Tom? I was, do you have any questions for me or anything or?

Tom: No. Great. Yeah, I appreciate that you are interested in talking to this old guy over here.

First Meditation Retreat Experience

Leafbox: Well, why don't we start with ,that my first question was going to be, aside from your 30 day retreat, looking back on, you know, I think 44 years ago you had your first 10 day, what would you tell yourself entering that first 10 day?

Tom: Yeah. Gee, let's see now. My first 10 day was actually in 1979. I don't know. I guess that was what would I, looking back on it what would I tell myself back then?

Leafbox: Or looking back, how do you think, was it the right decision to join that 10 day, or?

Tom: Yeah it, again, it was also biting off more than I can chew.

I think this is sort of like a recurring theme with me. I I tend to get excited about things and want to go, you know, full on, like 100%. And like I got interested in Buddhism, and then within about a year or two, I was in Asia, you know, and signing up to be a monk. So, yeah, so that first 10 day retreat was I had no idea what I was signing up for and when I after about the first day or so I kept thinking to myself, there's a there's a comedy duo from the 30s, 1930s or so, or 40s, and it's a recurring theme where you have a person of large stature and another person of small stature, and they have a banter between them, and the larger person would say to the little, the smaller person This is a fine mess you've gotten into us now.

So I would say to myself, Tom, this is a fine mess you've gotten yourself into now, because I tend to jump in over. Yeah that 10 day retreat was very challenging. It at the end of every single one of these experiences that I've jump in over my head I managed to find a way to tread water long enough to the end, and then I say I invariably have the feeling, boy, I'm sure glad I did that.

That was incredible. It was just amazing. And that wasn't the felt sense of the experience about 99 percent of the time. The felt sense of the experience was, this is ridiculous, this is so damn hard,. So then, you know, then the notion starts to form that what we're taking as the feedback loop from our mind , what we're evaluating and what we're judging and what we're comparing, is only a very small part of our of our mind, and it's the part, unfortunately, that has colonized the rest of it.

So we have this little part here that, has planted the flag of me, and has claimed ownership of this whole thing, and then when things don't go according to the dictates of this little me it starts to be a problem and it starts to complain. But in actuality what's been happening is, I've been noticing, is the larger part of me has had an inclination that the types of things that I throw myself into are ultimately really challenges that are actually, in the end, going to be quite beneficial.

But during the whole time that I'm there, like, I don't have that I lose that perspective because a little part of me Is having a hissy fit and is saying, oh, this is too hard. You know, I should have tried a different retreat. Or you know, or maybe I should go for Sufism, or, I don't know, Scientology, I don't know something right?

But, so the same thing, I here was 45, 44 years later, and I jump into this 30 day retreat, which I'm on the surface of it, you know, seems like, well, I've done these before, I should be fine, but I hadn't done one like this in 28 years, because, In that 28 years, I've been working full time as a nurse and all the sort of sorts of stuff.

And then again, you have this little part of me that's saying, oh, this is ridiculous, you know, I shouldn't, you know, and then towards the end is like, man, that was so powerful. I'm so glad I did that. I don't know. I don't know what the what the implications of these are. It's just that I'm, what I'm, I think I'm saying is that there's a part of our psyche, which has an intuitive feel that some of these things are ultimately beneficial, but then there's a part of us that is reacting because it's lots of the things that we intuit as being beneficial are causing a lot of discomfort to you know, how we've sort of habitually set ourselves to our reward system up in our minds to, you know, enjoy a good meal, enjoy a, you know, a film every once in a while, or, do some of these things which, you suddenly are not allowed to do when you're in, in, in a situation that's challenging to your ego.

But, yeah by and large, your question I don't think, I don't think I would have said anything differently other than you know, you've only got 45 years left. Just go for it, dude.

Life Journey and Early Influences

Leafbox: So, Tom, why don't we start before? Where did you grow up? Where are you now? Where are you in your life? What's your major projects you've done? Maybe rounding with your nurse work in Aloha Sangha.

Tom: Yeah. Okay. So I grew up in Panama, Central America. My mother's Panamanian. My father was connected with the the expatriate community who were employed by the Panama Canal system.

So, I grew up bilingual, bicultural. I had a kind of like a very sort of, normal kind of upbringing up upbringing where I didn't have very good parenting . I did not, normal meaning average. I, in adolescence, I began to question lots of ideas that were never explored in, in, in my upbringing.

So then I got into exploring different religions and different points of view. I grew up Catholic, and no one was able to answer any of the basic questions that I had about Catholicism. They just said, well, we don't know, and, you know, this sort of thing. You know, does God really have a beard?

Does he really have a throne? Does, etc., all these things, you know, I was and about the community of saints, I was thinking, do, there's like, I don't know, in Latin America, there's like literally hundreds of saints. You know, there's like a patient saint of this, a patient saint of that, and so I was curious about it.

Discovering Buddhism and First 10-Day Retreat

Tom: But anyway make a long story short, when I got into high school, I kept going through the different books in the high school library, and I was reading on different things, and I came across this book called What the Buddha Taught by a Sri Lankan monk named Walpola Rahola. It was printed, it was published in the 50s by a small publisher called Grove Press, and that book has been in print for 60 some years, and it's a really, excellent presentation of Southern Buddhism.

And when I read it, I kept looking for like, okay, so where's the part where you have to have faith and you have to worship? I kept going, turning the pages, waiting for something, and at the end there was like nothing. I go, wait a minute, this is a religion about. trying to be a good person and meditating, but there's no mention of heaven or hell.

There's no mention of worshiping a deity or anything. I go, what the hell kind of religion is this? Wait, there's nothing here. It's like, you know, and then it dawned on me there really wasn't a religion at all. It was more like a way of life. And then so I was really interested and So from then on you know, I I got through college on the easiest way I could because I grew up speaking Spanish, so that was the easiest thing, so I became a Spanish major, and I didn't know what to do for a living, and so I happened to be in Southern California, and I heard that people who can speak Spanish really well, i. e., you know, people who have like a Spanish major degree might apply as a court interpreter in the courts, and I did that, and so, so I was working in Los Angeles as a court interpreter, and it turns out that just a few blocks away, there was this Sri Lankan temple. And I went, because I was thinking, gee, you know, I remember that book in high school, and back then there was no internet.

There was the white pages, or the yellow pages, and I happened to look, okay, that author was from Sri Lanka, so I looked at Sri Lankan temples, and it turns out there was this temple just a few blocks from where I was living, and so, I started going there, and yeah, from that's how I got interested in these retreats, and then that's how I did my first 10 day retreat in 1979.

Leafbox: What did your parents think of you going to Sri Lanka for your first sit?

Becoming a Monk in Sri Lanka

Tom: Yeah, well, that, that created a lot of yeah, so it was 1984, so it was like five years into this I, or 1983, something, I think, no, in 83, I did the, in 1983, I did this thing called a three month retreat, which is this annual intensive retreat that's held in one of main centers for Western Theravada or Southern Buddhism, and so they thought that I was joining a cult, and then after I told them that after that retreat, that three month retreat that I was going to Sri Lanka to become a monk, they, you know, like, my father was like, I hadn't, he basically just. wrote me off. It was like, okay, this guy's this guy's gone crazy or on me or whatever. So, I basically, it was ten years before I had any more contact with him. My mother thought I was just being, you know, sort of like a romantic you know, following my bliss kind of thing or whatever.

So, she was okay with it, but, Yeah, so I did that for three years, and then I came back, and I went back to being a court interpreter in Los Angeles until 1990, and then I got got to a point in my life where I just needed to change, and moved to Hawaii is a long story, but then when I got here, I met the person who's now my wife.

We've been married for 30 gosh, we've been married since 1994, so that's about 30, 30 years.

Leafbox: What was Tom, going back to Sri Lanka, what made you ordain as a monk? You were fully in it then.

Tom: Yeah, that's the thing is I just wanted to, I figured that that if you wanted to experience something, you have to do it fully, you know, so, you know, there weren't any actually, back then in the 80s, there really weren't any places for Westerners to go to practice meditation.

There was a few places that, and it was it wasn't really a thing back then. So the only thing that you could do is you could go and approach, you know, a monastery and you know, sort of apprentice yourself to them by like living there and and essentially you would have to do, you'd have to do is you have to learn the language.

In other words, you have to learn in Sri Lanka, the main language is called Sinhalese. And so, There, there wasn't any, nowadays, because meditation is so huge now, and mindfulness is just this huge deal, there's dozens and dozens of centers that cater to Westerners, because they know that Westerners are really interested in this, and they'll go there, and they'll spend money, frankly.

So, but back then, it wasn't a thing. So, so, and I knew that beforehand because I was talking to the monks at this temple, and they said, well, there's nowhere, the only thing you can do is go to and they suggested I go to this one monastery which they were sort of, had some affiliations with, and to just show up there and say, you want to learn meditation, you want to practice intensively, and The, on the, there was only two teachers in that tradition that, that were that, that were good at teaching meditation.

And neither one of them spoke English. And the other thing about it was, okay, wait, this is an important point, is that many people in the west think that when that Buddhist monks in Asia all practice meditation. Well, when I went there, I found out that only perhaps. one or 2%. And I'm not exaggerating.

There's a tiny fraction of Buddhist monks and nuns who are in it because of meditation. Most of them, the vast majority, are in it because it was sort of expected for a member of their family to ordain, or they came from very low socioeconomic classes, and it was one way to somehow. Lift up their social status to have a son or a daughter, or they were in it because they wanted an education and they couldn't afford private education.

And so the vast majority of monks and nuns in Asia that I found are engaged in social service projects, like they're teachers, or they do things like what we call social work, or they do things like like, what you'd call a counselor, people who come to them with their problems, and this and that, but only a tiny fraction, so for me to find a meditation teacher, and Sri Lanka was no easy thing.

And so it, if you were in Sri Lanka in 1983 and you wanted, or beginning of 84, and you wanted to learn meditation you had to affiliate yourself with a monastery. And while you're there, You have to observe all these precepts and wear white and shave your head. So, that's just what you do. And then, after about six months there, if you haven't ordained as a monk, then, you're, they think less of you.

So, that was just it wasn't any, Like, I went there because I wanted to learn meditation from an authentic source, and there was no other options for me, and it just felt natural. And then when I was there I was taken in by the community. I felt very welcomed and very well taken care of.

It was a very welcoming, very nurturing, and once I got the lay of the land in terms of the language, I, you know, I wasn't fluent, but I was able to like communicate, you know, somewhat. Okay. And yeah, it was fantastic. It was a life-changing, incredible experience.

And that's the only way that I was able to experience some of the deeper aspects of meditation. You know, in the West at that time, in the 80s, there was a chance to do 10 day retreats, and at the most ahead was a three month retreat. That was it. But when you're in Asia, in a monastery, especially a meditation monasteryby the way, there's hundreds and thousands of monasteries inlet's let's just focus on Sri Lanka.

There's hundredswell, there's thousands. Only a small fraction of those have dedicated meditation teachers and, you know, just a small fraction. So to pursue, like, the deep end of meditation, you'd have to do, like, a three month retreat and then wait around, like, nine more months for the next three month retreat.

There wasn't anything in the West for that. But when you're in this situation in Sri Lanka, they're doing 12 hours a day, every day. You know, 365 days a year. And some of those monks are like really highly mature, very deeply developed meditation, meditators and meditation teachers. So you're throwing yourself into this thing.

This 365 day training regimen that was, that would be like impossible to access anywhere else. You know, back, at least back in the 80s, you know, now you have, you know, more intensive retreat centers here in the last 10 years or so you have places where you can go like all year round and meditate, but that was not the case back then.

Deep Dive into Meditation Practices

Leafbox: What were some of your experiences? For people who aren't familiar, I've done a 10 day, a few of them. know, But what happens after the 10 days,

Tom: yeah, okay, so that, that's a fascinating, that's an incredibly that's an incredibly fascinating question. So, but I'll try to make it very succinct, because I could go on for, you know, most people will go through initial period, which I described earlier, where your sense of, , comfort and sense of, like, rewards and what find rewarding in life.

It often has to do with pleasures of the senses, like eating certain things or, you know, having recreation, having good relationships, all these sorts. All that stuff is not happening, right? Because you're basically spending 12 hours a day meditating, and that's either sitting still for one hour periods, alternating with 45 to 50 minute periods of walking very slowly, and then eating very slowly, and only eating one meal a day, by the way.

So you're, you're not getting your jollies from eating. You're not getting any kind of like happy vibes from recreation. Nothing, it's like nothing, right? It's just like you're just focused on paying attention to your breath and paying attention to the sensations in your feet when you walk.

This is like the main method. So what happens is, you know, after about five, six, seven days, you start going crazy, going, Man, this is, you know, like, I feel like I'm in a, you know, like, my one fantasy was that I felt like I was, I call it a concentration camp. You know, it's a pun because, you know, like, like you're locked up in a camp, like, you know, and like, I don't know, Nazi Germany or something.

It's just, you know, it's a horrible situation. But you're also there because you're concentrating on your breath. So, so you have this thing where you're adjusting to the fact that you've got a highly limited area from which you can get your dopamine hits, you know. And then what happens is you you know, what normally happens is you're given the task of noticing how you feel in your body the sensations of the breath as you breathe in and as you breathe out when you're sitting still for an hour, right?

And some people feel it in the chest, some people feel it in the stomach, doesn't really matter where. And then what happens is that your mind will start, you know, jumping around and then it'll settle, like, like after about 10 days your mind, well, this is like a gross simplification, but your mind will start to settle on the direct present moment experience of the sensations of your breath.

for longer periods of time. Initially, it might be for, you know, half a second, or two seconds, maybe three seconds. Then you're off in some fantasy for like, you know, minutes, and then you go, you notice, oh, I'm fantasizing, or oh, I'm catastrophizing, or oh, and then you come back. Okay, so after an initial period of adjustment, You're able to remain focused, so your your capacity for focus improves tremendously.

So your baseline capacity to attend to the present moment's experience expands tremendously. tremendously. And then what starts to happen is when you're you're mind and your body, well, you're, is more acclimated to being, to remaining grounded or focused in the present moments of experiences, and you, of course, the present moment's experience changes, so what you're doing is you're sort of riding a wave of what's happening in the present moment, and as you ride that wave, you find yourself less and less in the alternative, which is what?

The past or the future, right? Obsessing about what happened in the past, and like, making all these plans, okay, there comes what I call a figure ground reversal, in psychology, whatever you see this picture of some people see a vase, or some people see two faces looking at each other, well, so, or these pictures where you're looking at this three you know, this obviously two dimensional image, but as you're eyes relax, you start to see a three, seemingly three dimensions.

You can see depth into this image. So, so that's what I call a figure grand reversal, where you're focused on the figure. But then after a while, you start to relax and you see the ground, so what happens is that rather than being obsessed with your wants, your needs, your fulfilling your so called needs by, getting, gustatory sense impressions or however you know, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, you start to get a tremendous amount of pleasure.

Not only pleasure, but well being in the simple fact of being alive. and aware in the present moment. And that's a huge milestone because then all of a sudden you start to feel so, you have an incredible sense of well being. Just phenomenal. And then you start to look back and go, Man, I used to really like, you know, I don't know, NASCAR.

I don't know. I used to like, you know, Bruce Willis movies, whatever. I used to like this and that, but man, I really love my breath. It's like, it's completely different. It's not just the breath. It's the fact that you've disengaged. from the fascination with the future and the obsession over the past. Those don't have any they don't call you the way they used to, and you start to notice how much mental energy was bound up with, fruitless ruminations over the past and equally fruitless preoccupations with the future.

And then all of a sudden this new area wells up of the present moment's experience, and that brings, number one, it brings an innate sense of well being that for most people was hitherto unknown, completely unknown.

The Bliss and Challenges of Meditation

Tom: But number two, It starts to bring something called in the language of Southern Buddhism Suka and Pitti, so PITI and S-U-K-H-A.

So suka just means happiness, but pti, PITI is a very interesting word, and that means rapture. And if you look into, if you happen to be so inclined, you could read into the Buddhist scriptures and or they're not really scriptures, but discourses of the historical Buddha that have been handed down for the past 2,600 years and bits and fragments and whatever, and you piece 'em all together.

And over the course of 40 some years the historical Buddha mentioned . Okay. 18 different types. of piti, of rapture. Okay, there's one rapture where, you know, like in Hawaii, we call them chicken skin, or on the mainland, goose bumps. , where, right? And then there's another one where your hair is, on your body is sticking up on end.

There's another one where you just have tears of joy just streaming down your face. And then another one is you have this but there's eight people who've spent years experiencing these different levels of profound levels of joy and rapture, have actually enumerated all these types.

And then what happens is, then you start to explore something called the Jhanas, J H A N A, which is a fascinating area. It's completely, it's a completely fascinating area. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. There is, okay, so after you have this rapt, okay, first you have this happiness, this sense of well being that's innate and that's inviolable, it's just really remarkable, then you have this incredible joy, like rapturous joy, and then you have these experiences that are categorized As four levels of there's no really good English translation, but the one word that is used is absorption, which doesn't make any sense really.

But what it is you get into this this, okay, let's call it a meditative groove where you're sitting quietly. And let's say you're paying attention, the classic thing is to pay attention to the sensations of the in and out breath at the nostrils or at the upper lip. So you start feeling these little tingling sensations as the breath goes in and little, maybe warmer sensation as the breath goes out because the out breath is a little bit warmer.

And you start to develop this microscopic level. Almost like nanotechnology. You're able to focus on these little, tiniest areas of sensation, and then your mind locks, it locks on to that, and then that locking on is such that you, it's like, like, you know, wild horses couldn't draw you away. Your mind is locked and loaded on this area here.

Locked and loaded means that you're basically absorbed, like your attention is right there. And if you had wild horses come, you know, they couldn't drag you away. Okay, so. What that does is that puts you in this level of concentration, they call it, such that people have been known to say, okay, I once you develop the capacity to have that level of concentration, you can make a determination in your head, like an intention, a willful intention, I'm going to sit down, enter the first jhana, or this level of concentration, and remain there for four hours and twenty minutes.

Okay, now this, okay, this sounds totally bizarre from a Western point of view, but people have been known and have been tested that yes, you can, it's almost like, have you ever heard of someone who has an important an appointment in the morning and they don't trust their alarm clock, but they'll say, I've got to be up at 6.30 I have to be up at 6. 30. And somehow the mind remembers that and wakes you up at 6. 30. Well, it's the same sort of thing. The mind, you've developed the mind to such an extent that you can will yourself into an experience that you had before, which is this level of concentration called jhana, and remain completely motionless, sitting quietly without any pain and without any sensation of even having a body for the exactly predetermined time that you set in as an intention before.

And, okay, so that's actually possible. I've actually done it myself, so I can tell you honestly that this can be done. And when you're in that level of concentration, this is called concentration, by the way this capacity. Some people call it focus, but when you're in that level of concentration, okay, this is going to sound probably inappropriate it.

But I'm going to say it anyway because there's no other way to explain this to people, right? And I've said this before and I've gotten some flack for saying it, but the honest truth is that when you're in that level of concentration and you, there's no sense of having a body, none whatsoever.

There's just this sense of infinite space and infinite peace. But on top of that, almost like it's stacked, you have infinite space, infinite peace, and per suffusing that whole experience is bliss like a mother. There's a bliss like you wouldn't believe, such that, if you were to compare ev every single, Previous blissful experience you've ever had, like for some people it'd be for me and when I was at in my late teens, it was going to a Grateful Dead concert.

That was the highest level of samsara. I was just going to a Grateful Dead concert. Two, having great sex with my girlfriend. Three, some kind of drug experience. Four, perhaps a beautiful sunrise or sunset or climbing a volcano in Guatemala and seeing the sunrise, which I did when I was an exchange student in Guatemala.

Every single previous experience that I thought was like the bomb, you know, the best, doesn't like, there's no comparison. There's like, it's like, Not only is it infinitely higher grade bliss, but it goes on forever. It's just like it's like, anyway, so, so those kinds of experiences, what I'm just describing are not too common if you do a three month retreat.

Okay, a 10 day retreat, you're not going to get that level of concentration. You're not. One month retreat, yeah, maybe. Three month retreat, you're starting, you're in the foothills. But this is talking, these are mountaintops that you can, you only really get to the first time. It's like you climb a mountain.

It probably take for most people to take, you know, six months, nine months a year before you can, you say, Oh, I, Oh yeah, now, because but the funny thing is once you climb that mountain, you can go back to it with, it doesn't take a year to climb that mountain again, it might take you three or four days or a day of retreat and you're back on that mountaintop.

You know, and that's the most remarkable thing. So that's, but see, that's only from the point of view of pleasure and bliss. Okay. Which really isn't the whole point of undertaking meditation practice. It's not. That's not the end point. It just happens to be Really helpful in pursuing the end point. Okay, does that add does that kind of give you

Leafbox: I was gonna ask two questions: What is the end point?

And then how did you come back down from the mountain? Okay, so you have a dark night of the soul experience.

Tom: Yeah, absolutely. Oh boy. Yeah. Okay. That's a really great question Okay, let me start with what's the end point? Okay, so There's okay.

The Ultimate Goal: Nirvana and Liberation

Tom: The end point is something called in the Southern School of Buddhism, they use the word Nibbana, N-I-B-B-A-N-A.

It's been, it's mostly known in the Sanskrit form, which is Nirvana, which is also the name of a grunge rock band. Now the thing about it is that Nirvana is not a place, it's not a ultimate. It's not a somewhere you go when you die. It's an experience that you have. Just like the experience I described of this incredible bliss that is completely incomparable with anything that most people have ever had before.

It's an experience that completely alters a person in specific ways. Okay, so, okay, so first of all, So the endpoint is something called n Nirvana. Let's just use the more popular Nirvana. Nirvana is an experience and Nirvana alters people now, okay, the reason why Nirvana, or having an experience, or, okay, let's put it this way.

Having an experience of nirvana. The reason why having experiences of nirvana is the endpoint is not because it's any more pleasurable than the bliss that I was describing earlier. It's not that. It's not that. It's because from the Buddhist point of view, the whole purpose, the whole reason you do meditation is, number one, to eradicate, they're called the three poisons.

It's as if all humans are born with a certain modicum, a certain bag of poison and pain that we carry in our body, in our minds which lead to things like addictions, compulsions, acting out, doing stuff that you regret later, , acting a fool, all these kinds of things are, can be attributed to you.

what they call the three poisons, which are greed, anger, and delusion. So, tendencies to act out in anger, tendency to act out with craving, and tendencies to be deluded, which means to, like, act really, you know, to not see things very clearly. So, so, you know, but when I say three poisons, they're really thousands of them, because each one of them has little tributaries you can you know, so it's just like, so, so the whole point of the whole meditative path is to become a better person by lessening, progressively lessening the impact of this these negative tendencies in our minds.

Okay. Now, what that means is that From the Buddhist point of view, once you, there are four, classically they talk about four experiences in nirvana. So the first time you experience nirvana, it's like a, it's like a lightning bolt, like, well, it doesn't have to be a lightning bolt, but it's a very specific experience that you it's you can't not know that you had a nirvanic experience.

There's no, and you can't fake it either. You can't, like, you know, okay, so, okay, so then, you know, if you train harder and harder, you can have what they call a second one. And this is also something that is borne out in the Mahayana or Zen training. They'll say you have a first Kensho, second Kensho, third Kensho.

Okay, so these are specific meditation experiences that happen that are like completely different from bliss, okay? But, okay, I can explain what a nirvanic moment is in a second, but to answer the question, the whole point is not to have bliss, But to clean out as a human so that you are lighter, you're happier, and you're not such a fool.

You are and what that means is that you become more moral. You have this natural sense of empathy and compassion, which wells up in you, because when you're free from the influence of these poisons, what they say is that the heart is cleansed of these poisons, and that compassion is inherent in the heart.

See, in Buddhism, it's very different from Christianity. Christianity talks about original sin. Buddhism talks about original innocence. There's a sense of original purity and original innocence, and that innocence or purity is characterized by love, compassion, and feeling of connection, empathy with others.

It's innate to their natural state. But because of the influence of these poisons, many of us act stupidly and do things we regret. So the when you have these blissful experiences, it doesn't lessen all, any of the poisons. It doesn't, it, you're still the schmuck. You're just a happy schmuck, right?

But when you have a nirvanic experiences, it does something to, it cuts the root. And I can't explain why I'm not a psychologist, you know, but it actually cuts the root of these. poisons in the body such that as you have progressively deeper nirvanic experiences, it becomes completely can't, I don't want to use the word impossible, but it becomes highly unlikely that you'll ever act out again.

And you see, I see, I've seen monks who are purported to have had second and third experiences of nirvana, And by the way, when I say second and third, I don't mean repeats. The second time you have it it's an exponentially higher grade level of the first one. And the third one is, it's not, you're not repeating it, you're getting a, I can't explain how this happens, but it really does.

This thing really works. This is what I'm trying to say. And so the point is to become a better human being such that you're more compassionate, kinder, and you are, you actually the whole point really is to get to a place where you're so cleaned out. You're so empathic and compassionate that you work for to help other people, to help other people who are suffering.

So the whole point of Buddhism is to become a better person such that you actually give back and are compassionate and help other people. That's the goal. But the bliss doesn't make you that. The bliss, what the bliss does. Is it gives you it's like a the way I, I like to think about it is, you know, you have a rocket that's like, let's say you're putting a satellite into orbit, and so, so you have a booster, right?

So this big rocket goes, and then after a while it falls off, right? And another thing, okay, so the bliss is like a booster. Get you up there, right? And once you're up there, then there's another fire that goes off. And then so you have to attain something called escape velocity, which is however many miles per hour, because if you can't get so many much more miles per hour, you're still in the gravitational pull of the earth.

So, the analogy I'm making is that, that from the Buddhist point of view, karma is our gravitational pull that keeps us pulled into acting a fool, or being, you know, unkind, or this is our gravitational pull, this is our karma, right? Or these are our poisons. So the bliss is like a booster, gets you up there, and then and then the nirvanic moments, gets you out.

Of the gravitational pull of karma such that you're free. So one of the ways that the Buddha described n a person who has attained at least the first stage of Nirvana that he's, he has become he's attained lib or liberation, right? In other words, liberation can also be called as freedom.

And so the analogy I'm giving of this booster and then this other thing is that you become free from the gravitational pull of the earth and in the analogy you become free from the gravitational pull of your karma. So there's a certain freedom there. And that's the real, that's the whole point of Buddhism is to attain liberation from your own poison and pain.

Your own crap, your own tendencies to act, in such a way that you're related to regret. And that's, so, but so, so the reason why the bliss is so important is it's that booster that gets you up, that gets you, and then after that, Then after you have these incredible blissful moments, you are much more, first of all, you're much more, you go, holy shit man, this is incredible

You know, so you kinda wanna keep going. And then so you know your teachers like, okay, you've had you know, bliss like a mother, you've had like level four Jana, now let's train you for Nirvana. Right? And so that's a little bit different kind of meditation that you do, which involves. like, it's more analytical.

Simple Steps to Achieve Bliss in Meditation

Tom: Whereas to get you to the bliss, the booster, is you're basically, it's really stupid simple. You just pay attention to one spot, like here, or on your abdomen. You just put your attention and stay. Just, and your attention goes, come like a puppy. Go, come back, go, come back. So it's really simple. But after you get the bliss and the booster and the jhanic states, that's where the meditation becomes.

It's not more complicated. It's just richer. There's more to it.

Analyzing the Self: Deconstructing the Notion of Self

Tom: And it involves analyzing how your sense of self starts to form and analyzing the self in terms of five constituents. And that the self you know, when you deconstruct the notion of a self, By analyzing into five different parts, you see that the self is actually not a self at all.

It's a construct. And then, so, so, these are and that's why I call it analytical. You're deconstructing and analyzing the whole idea of being a person, such that you start to realize, gee, maybe I'm not such a solid, thing that I've taken myself to be, right? And so for some people that sounds frightening, but it actually can be very liberating because you have a sense that, you know, you're not bound by, you know, what you think yourself to be all this time. So you're basically deconstructing yourself a little bit by a little bit by a little bit. But it sounds frightening to some people, but it actually it isn't. It's actually quite liberating.

Meditation for Beginners: Awareness and Intention

Leafbox: But Tom, I think all of these things you're talking about can be useful for people who even do a one hour sit.

Even your first beginning sit, it's just awareness of the self, awareness of non duality, awareness of the ruminations, awareness of bliss, and then hopefully, a cleansing of motivation and intention for others. These are all things I've experienced in just even a short meditation session.

Tom: Absolutely. Yes, absolutely. Yeah, absolutely. That's why meditation teacherI'm sorry medtiation teachers who are worth their salt will incorporate the whole path into meditation. You know, so people are aware, just like you said, Robert, you said it perfectly. Yeah, exactly.

The Evolution of Meditation Practices

Tom: If you know, so we are the recipients of a lot of Western meditators who have gone very far to these mountaintops and come back, et cetera, and are able to, like, synthesize the whole thing, such that the whole path that you just described so eloquently just a few moments ago.

That whole path can be at least, you become familiar with it just in maybe even a half an hour of meditation, you know. And so lots of teachers these days will give you guided sessions where you start like basics like, and then you start to, you know, make these suggestions about,, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

But you had asked me, you know, like, you know, what sorts of experience does people usually do people have like after 10 days and after three months and so, that the kind of experience that I was explaining a little while ago about the booster and all that, that would have been impossible.

For me, in 1981 in the United States, it wouldn't have been possible. I don't know of any place that I could do that. So I, you know, I had, if I wanted that back then, I had to have gone to Asia. I would have had to have gone to Asia. But nowadays, thankfully, we have, in Massachusetts, there's A place called the Forest Refuge, where you can actually sign up for like, you know, like nine months or a whole year.

You can spend a whole year there. You know, it's gonna cost you money, but it's, I think it's, you know, reasonable. There are places in the west where you can actually do that nowadays.

Leafbox: So, so going back to my second question, maybe for people, the dark night of the soul experience.

How to return to your non monastic life. How is that?

Tom: Yeah, okay, yeah.

The Dark Night of the Soul: Understanding and Coping

Tom: The Dark Night of the Skull is very real. It's very real. It's taken from the writings of St. John of San Juan de la Cruz, for those of us who speak Spanish, and it's very real.

There are and I don't profess to know the psychological ins and outs of it, but from my experience, because, oh yeah, I've had, I've definitely experienced There is one particular style of meditation that, for me, elicits this dark night of the soul. And so, for people who may not be familiar with the term those are experiences where you feel Well, one common experience is a feeling of alienation, even from yourself.

A feeling of well, put it this way, depression or Yeah, depression a feeling of loss of a sense of pleasure in things that you've previously found pleasant which is called there's a fancy word in psychology it's called anhedonia, which is, comes from the word hedonism. And anhedonia means that your experiences are essentially flat.

You don't, you know, things that would previously give you joy just And so these are common experiences in people who haven't, who've either gone a little bit too far and weren't given a lot of grounding in the basics or who've done a particular kind of meditation that was paced a little bit too intense and just let me tell you that Now, by, by what I'm about to say, this is not a judgment or a value statement about a certain kind of meditation, but there's a certain type that's being taught in 10 day retreats that involves a scanning of the body up and down.

That kind of meditation for me put me in a really kind of deep states, but then I didn't have the grounding. And I think I did five of those. And after each one, I came out going, feeling like, like, like. Like, feeling like something was really wrong. Like, I felt, one of, one time I just felt like all I wanted to do was just drink beer and just like, just, you know, like watch movies all, I just wanted to like numb myself.

So, and so I, I don't want to turn anybody off, but, and I want to, I don't want to impugn any particular kind of meditation, but that particular type really did a number on me. And I realized that when I went to Asia and did If if you don't have enough grounding in the bliss of the the sense of well being and sense of joy that comes from naturally disinclining the mind from ruminating and etc and processing the past etc., and like resting in the pleasant moment, that sense of well being and joy. If you don't have, if you haven't, like, really experience that such that it starts to do what I call the figure ground reversal where you actually feel more joy and more ease from being with what's happening versus what I want or think should be happening.

You know, that's what I call this figure ground thing. And then when, if, when, once that becomes like part of your heart and soul, it's you have something to fall back on. If you start feeling alienation. from these deeper states. And so, so the, so, okay, so, yeah, so the dark night or let's call it unpleasant or unpleasant Yeah, unpleasant or uncomfortable experiences from deep meditation has actually been studied now.

If you go on to any search engine, you start looking at the you know, the dark side of mindfulness, you'll see quite a number of of of scholarly articles that have actually talked about, you know, these sorts of alienating experiences some people have from doing, not just doing like, you know, an hour or so, but I'm talking about 10 day retreats where you don't really are given a lot of grounding.

Yeah, so I've experienced those, but then once, well, once I really was able to, like, settle into the the sense of well being and bliss that I would get I had that to fall back on. So the sense of alienation would just sort of, it wouldn't, it would fizzle because I would have the sense of well being I could tap into.

And for me, just, you know, an aside. Okay, so the meditation style that I basically been concentrating on for like the past 40 some years, just to give you the term, it's called the Mahasi Sayadaw.

Grounding Techniques in Meditation

Tom: It's just one approach, but the beauty of that approach is it's very grounding because you do one hour sitting, but then you do one hour walking.

And the walking can be very, well, as the name implies, can be very grounding. But it's grounding because you're out of your head, you're in your, you really feel your body. It's actually about feeling your feet on the floor, actually. Basically, it's about feeling for an hour. Well, actually 40 50 minutes, because you do an hour sit about 45 minutes.

For those 45 50 minutes, all you're doing is paying attention to your feet as they lift and place on the floor. And that, okay, it sounds very boring, but, you know, it's extremely grounding and you can feel this. sense of deep well being. And the meditation system I was alluding to before has no walking in it whatsoever, those 10 day retreats, right?

So I think that's one of the reasons. But nevertheless, there were times in my practice that I did feel these, definitely, and I was only able to resolve them by I trial and error, and I found that to me the walking was really helpful in getting out of those kinds of states that are uncomfortable.

Leafbox: Well, Tom, that was one of my questions I was going to interrupt you. Sorry. One of the things I appreciate about your teaching is that you're quite eclectic in your style, and you pull from different traditions. Whereas, you know, your critique of Vipassana style, for instance Yeah, usually they want you to only do this, or if you do Zen, they want you only to follow their traditions.

I like the Buddhist buffet. Other people are very critical of the Buddhist buffet, but Yeah, one of the things that, maybe because you went from a Western perspective to Sri Lanka, how do you approach teaching? You've been pulling from all these traditions.

Tom: There, one of the reasons why I like to pull from other traditions is because don't feel that the Southern Buddhist tradition has all the answers.

It has answers, it has particular techniques to do a particular, you know, to bring about certain results. But for some people, it can be very helpful for them to feel that That no one tradition holds a monopoly on truth or understanding reality, which I don't think, I think, the, in, in looking backwards the Buddhist tradition that I follow is a little bit lopsided, because they're you know, so, I really, for example, like to talk about the within Hinduism, for example, There's a a heavy within some Hindu traditions, there's a heavy influence on the householder life or, being a having a family and then you go to Sri Lanka and they're all about being monks and nuns living in huts.

That's not. And so, there's like Sufism talks about love and compassion and, you know, different traditions. And what I think is that If we have a particular approach to meditation that seems to be working for us, if you are like you say, if you make reasoned choices from the banquet that's available out there, it could complement very nicely the main course that you're teaching.

You know, so, you know, and, but the other reason why I don't like to present, let me give you an example. I don't want to name names, but there's a a, there's one way of teaching which is solely focused on, you know, this is it, this is the Mahasi approach, there's rising and falling, lifting when you play, that's it, nothing else,.

That's not really helpful. That kind of creates like, you know, these little, you know, you know, meditation robots. I don't know. You know, so I said, Buddhism doesn't hold all the answers. It has a very nice path, but that doesn't mean you have to, like, do it hook, line and sinker. You can do the techniques, but you can also adapt it to your life and your own particular outlook on life , in whatever way it suits you.

You don't the other thing, the other reason why I like to draw from different traditions is just so that this is more selfish, but I just want people to feel comfortable, you know, that they're not coming like to, you know, we have these things, these weekly meditations groups that are at my home, and I don't want people to think they're coming to a cult, you know, so I don't, you know, I don't like to like say, this is the way, this is the only, you know, that's it's nonsense, you know, because, Everyone says that, and it can't all be true, right?

Leafbox: So, Tom, why did you start Aloha Sangha? What can you tell us about the history of that, and why you started it?

Tom: Well, yeah, we started in 1998, as a matter of fact. So, what Aloha Sangha is basically myself and my wife, we you know, 6 to 7. 30 p. m. It's free. And we do oh, about 15 20 minutes of stretching, or qigong kind of thing.

And it's a kind of like a, like a light yoga thing. And then we do two 25 30 minute periods of meditation. And then that takes up about an hour. And then we have, we'll break, and then we have about 20 minutes of just talk story. I'll give a little talk, whatever. So we've been doing that for 28 years.

So the reason why I did that was because I didn't feel that there were any options for people who could come somewhere who didn't feel like there was. signing up for some kind of a Buddhist thing. Because the only other places at the time were like saying, were like mouthpieces for some Buddhist tradition, right?

Like either you go to the Tibetan place, well that's all Tibetan Buddhism. You go to the Zen place, that's all Zen. You go to this other place, well that's all this kind. I wanted it to be like More about aloha, which is like, you know, love and compassion, and sangha just means like a group of people. So a group of people come together in the spirit of love and compassion, rather than a group of people who come together to practice this particular technique, you know.

Very different, so, And sure enough you know, there are people who have been coming years and years, and they say the one reason why they come is because they don't feel like they're being preached about, preached to about, you know, that this is the only way or this, you know, kind of thing. Of course, I, even having said that, I am if you, if push comes to shove, I do feel that the Buddhist approach to meditation has a lot going for it.

But that's not to say that you need to become a Buddhist or believe in Buddhism or anything for it to work. That's, you know, so that's the whole, that's the whole reason.

Leafbox: Yeah. No, I really like it. I think it's interesting just in my own personal experiences that I started with Vipassana and then I had some Zen training in San Francisco. And yeah, I've had some experiences where they don't like, if they find out you did Vipassan or if they really don't like you surfing a long board and then a short board. They don't like that. They want you to choose. So I really approach, I think yours is like an MMA dojo.

You know, like I said before, karate is welcome. Judo's welcome. Yeah. Everyone's welcome, but it's still a dojo.

Tom: Wow, that's a great analogy.

Leafbox: Yeah, I think like MMA style. So people you're still training together. I was going to be curious, how was you going back in time?

You leave the, you hit Nirvana or attempted first, second, third, I don't know what stage. How was it coming down from the mountain and coming back into society?

Tom: Yeah, well, well, I, yeah I wasn't, I didn't do that great. No, seriously, I had a lot of issues. I had a lot of issues. I actually, I don't know, did I ever tell you I actually went through a a period of time where I had a major depression?

Leafbox: No I know that, so I was going to, you know, maybe I touched that because I think people think Buddhism is going to solve all their problems, but I think it just makes you more aware of them, maybe.

Tom: Yeah, it makes you more aware of them, and I actually, one of the things that was coming up for me was like a a huge part of my life that I was sort of unexplored, that I was, even though I was having these incredible experiences, whatever it, One of the ways that, you know, I talked about the analogy of like, clearing the three poisons out of your system, you know, greed, anger, and delusion, and one of the ways that this Vipassana does it, it's like a dredging operation, where it just dredges things up, and then, hopefully, as they're dredged up, then they're processed, and then they start to disappear.

Well, for me, There was a dredging operation, sure enough, and but the processing at, for those issues to dissipate was, I didn't give enough attention to that, and I didn't realize that I was really good at dredging, but I was not very good at processing out. So I dredge up a lot of stuff in meditation, and I would, and because I dredge things.

What's the word? Oddly enough, by dredging things, you feel lighter, and it's a lot easier for you to experience these higher, so called higher mental states, etc., etc. So I was able to, like, go really high up this mountain, and have, you know, these incredible experiences, but I wasn't so great at processing the material that would come up, and I would, unbeknownst to me at the time, what I was actually doing was, I was, packing them back down.

So the analogy I use is composting, right? If you have garbage and then you compost it efficiently, it actually turns into organic material that can be used, you know, for gardening. But if you don't compost it properly, it just turns into like this smelly, you know, it's not useful, right? And so I wasn't composting Very well, and it wasn't until I had a a series of very profoundly depressing experiences that it became obvious that I was Something was not being efficiently, there was, like I was good at, like, hammering and breaking, but I wasn't good at, anyway, so to make a long story short, I ended up going through about a year and a half, two years. of weekly psychotherapy, and that was immensely helpful, such that I realized that I had a lot of enthusiasm for mountain climbing, but not very good enthusiasm for what's the word packing out what I brought in. I don't know. So, yeah, so There's pros and cons, so, but I don't want to give the impression that well, the impression I want to give is that meditation is something that needs to be done with a lot of care and a lot of understanding of what is actually happening.

Which I didn't have back in 1983 or 84 because I didn't have any psychological understanding whatsoever. All I knew was that I was supposed to climb climb, and then everything would be great. I'd have these experiences, whatever. But I didn't realize that that there was this whole other part of meditation which is you need to really be able to deal with the material that comes up.

And so, but what that really means is that You often times will have to be sitting in meditation and experiencing, you know, fear, anger crazy stuff that comes up in your mind in a way that you, first of all, make friends with it. Second of all, don't push it away. So what I was sort of, I was conditioning myself that whenever something unpleasant came up, I was going to push it away and just aim for the, you know, high.

And it wasn't until I realized That was only half the work, you know, I had to deal with the demons, right? And so most people who live like normal, functional lives have demons, it's just that you're not you're not poking them with a poker, a hot poker, you know, but when you do meditation, you start poking around and these demons started acting out, right?

And I was all about, okay, demon. Go, right? And so, but then I realized that the other, so it was really helpful for me to to do the hard work. There's a a line from the Irish poet Yates, Y E A T S, Yates, Yates, whatever. He said it's like, That, you know, what he's saying is that spiritual progress is going into the marketplace and visiting the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

And he's talking about like, like, you know, like in the old days, they didn't have refrigerators, so you have all this rag and bone shop. He's talking about like the raw meat hanging from, so it was like I was dealing with a lot of raw meat in my life that I was not processing.

Leafbox: No, I agree with you. All the sankaras come up, especially as you get deeper in.

I was curious, yeah, they really, when you do a ten day, there's not much support in terms of what, what can come up. So maybe that's one of the risks for meditation that, especially with mindfulness, they don't really approach that. So what tools can people, so you think psychotherapy is useful, what other ways, how do you deal with these sankaras?

Tom: Yeah. Well, yeah. Psychotherapy isn't, necess isn't I isn't necessary. Un. Unless, isn't like a prerequisite isn't something that I would say, okay, sign up, do meditation, and also do therapy at the same time. It's it's not like, you know, you have to have both going on.

I only decided to go to psychotherapy because it was clear that I was. Really depressed. I was like, I was really depressed, but something was going on, right?

But I think for me it was a case of just like you said I was going in Well, like I said at the very beginning of this interview is I have a tendency to jump in over my head So I was going in way over my head. I was going really deep I was like stirring all this stuff up and I was ignoring it and I was just going for the going for that gold ring at the whatever's around the nose of a horse.

I don't know, something, you know, I was going for. And anyway so, at the time, you know, I was a single male without, you know, you know, a grounded relationship. And this is one of the problems with meditation in Asia is there's no sense of being in a relate. You're you go to a monastery to to like, renounce the world, right?

The Importance of Balance in Life and Meditation

Tom: But you can't go into a monastery to do meditation and renounce the world with the intention of coming back into it and living, you know, a productive, you know, contributing member of society if you've So, I think having a ground, a very healthy, And understanding relationship with someone, you know, a deep, loving, compassionate relationship where you can, you know, each other on your stuff, you know, in an appropriate way, et cetera, and having like, You know, the other trappings of the good life, like having a good set of friends that you, all these things that make up a good life are so what I'm trying to say is that it's important not to, like, focus, put all your eggs in the meditation basket, thinking that's going to be the answer, that's going to help a lot, but you also have to have your life In order to, you can't just like ignore everything and think meditation is going to answer all your questions, all that, you know, be the answer to all your problems or concerns or whatever.

So I'm not sure what the, you know, I'm not sure if I'm answering that question very well, but

Leafbox: No, I think you did. I think it's just the approach of, I think there's a Japanese word called Ikigai, which means, I think, eight. pillars of life. Like you said, you need the family, you need the spirit, you need the work, you need all these elements to make a balance.

If you don't have the Ikigai balanced, then it's going to fall apart. If you go too into the spiritual, you ignore your earthly responsibilities or family or whatever.

Tom: Yeah. And that's what I was doing. Yeah. That's what I was doing. Now in hindsight I realized that I was forced into that understanding because it was, it came to a head.

Like, I was like, what, you know, am I, what's going on with, you know, I'm actually, you know, anyway, but yeah that's perfect. And so, you know, I would say that that if people, you know, have a, have their eight pillars together, or whatever, and you do an occasional retreat every once in a while, but but I think the most important thing is not to get too focused on what I was saying about the booster and the leaving karma behind and all that stuff.

That stuff, I think, will happen over time, and you'll be your own, you know, you can judge when it's the right time to go into, like, Explore intensive meditation. Certainly a ten day retreat once a year can't hurt. I think that'd be really great. The other thing which I think is really great is for people to actually have a, like a, explore having a committed, daily meditation practice of even 20 minutes and if 20 minutes works for you in the morning, you know, at some point you can add another 20 minutes in the evening.

You know, these sorts of, and then in the meantime, you know, having a sense of establishing a sense of being in tune with the present moment such that you develop this, what I call this well being and the sense of. happiness that isn't based on conditions being a certain way. There's a certain, you know, innate quality of fulfillment and happiness and joy that comes from simply settling into the present moment's experience, aka mindfulness.

So, yeah.

Leafbox: To jump angles, I know I don't want to take all your time, but I'm curious how all those tools have Your role as a father and then your role as a nurse, because you worked 25 years as a psychiatric nurse. I'm curious. Yeah. That's not an easy thing to do, so. No. Yeah. And being a father is hard too.

Tom: No, being, being a father was really huge, and getting married, having kids was really huge. Having a job was really, it was necessary because, You know, I, we put our kids through private, you know, private school here and then college and all that. And I had to work full time. There was no way I could take off and do retreats like some people, you know, are able to do.

But I having a full time job made me do was, made me realize that I had to make, find a way to make meditation work for me because I didn't have the crutch, the crutches of, you know, like saying, okay, enough, I'm going off for, you know, 10 days. I didn't, I actually didn't do a 10, okay, so there's actually 28 years that I worked at the, at this hospital, okay?

So between the first day and the last day, which was this past October. I didn't do, the longest I ever did was in one day in those 28 years. I didn't do anything long. I didn't have the chance. Not only that, but because I had a family, I wouldn't want, I wouldn't want to like run off for 10 days and miss 10 days of the life of my kids, right?

I didn't want to do that. I thought that was totally selfish. I wouldn't want to do that. So, you know, it made me sort of re evaluate how can I make progress and the way it worked for me was to do daily meditation. And to really work on, like, feeling grounded in my body and, you know, having the sense of well being that comes from orienting to the present moment versus, you know, passing the future.

And so just simple mindfulness and, it's actually very simple simple mindfulness in daily life and you know, 45 minutes for me was 40 minutes worth of meditation, sitting quietly. plus doing some walking meditation. And then I also had to add some exercise because doing exercise mindfully for me was really grounding.

So, all that, you know, all that worked. And I don't think that I honestly question whether if I had done it differently, I would feel as good as I feel about myself now. Because I think had I done what some people do, and I call them it's like they, people who are creating spiritual orphans, they have kids, but they're basically orphans because their parents are out doing retreats left and right, and they're, you know, they're not really orphans, but you know what I'm saying, right?

So, had I done something like that, I think I would have felt better. You know, I, of course, you can't go back and say what your life would have been like had you done X and Y, but I feel really good right now as a 68 year old retired guy that I raised two kids and they turned out great and I worked 28 years at the hospital etc.

I feel really good,

Leafbox: I think it all comes back to balance, like you said, pulling the eight pillars. What's the future of Aloha Sangha, Tom?

Future Plans and Spiritual Reflections

Leafbox: What's the, what's post retirement life for you? What's your next mountain?

Tom: Yeah, you know, what I really want to do is see if I can put together either one day or weekend retreats, and I'm looking at this place in Kahuku as a possible, I gotta go check it out again, some more.

And the other thing is I want to probably, you know, like I, I mentioned earlier that I, this is like the second or third time I've been on Zoom in the second, so, you know, people are asking, you know, so I might do something like this, like once a week no but now that I'm retired, I really want to give, put more energy into our group and offering what I try to offer, which is like a non traditional approach to Buddhist influenced meditation,

Leafbox: Great, yeah, I think it's a very successful project. I'm looking forward to the next development. And then Tom, maybe my last question, maybe on a more out there path, what's your relationship to spirituality now as a Buddhist? What do you, as you get older, where do you feel the woo, do you think there's an afterlife, what do you look at it as a Buddhist perspective, do you, going back to as a child, the Catholic faith, what, where do you stand on these larger questions, or is it all non dual, we're all connected?

Tom: Well, quite frankly I am sort of an agnostic. There, there's a lot about Buddhism that is unverifiable. They're basically truth claims that you, there's no way to verify in terms of like karma and rebirth and all this sort of thing. I am a little bit of a skeptic. I've just naturally been that way.

But I also have a tendency towards what you just referenced as non duality, where you know, there, there is a sense of, like, profound okayness about just, Okay, there's, the fact that we're alive and able to talk to each other, to me means we've already crossed the finish line. There's nothing else we need.

All this stuff is like embellishment that's, that at one point is absolutely ridiculous. Not necessary, but we think it's necessary, and by doing all the stuff, we realize it wasn't really all that necessary to begin with. So there's a, so the end point of the path is at a zero distance from the beginning point.

So, but it took me 45 years to really profoundly appreciate that. So, for me, it's more about, like, realizing that there's some of that these so called questions about an afterlife and are basically unanswerable, and they really don't mean a whole lot, because the present moment's experience, as it is for me right now, is so profoundly astounding.

I call it the astounding nature of the present moment's experience. I call that to myself. This is like my own jargon I use to myself. I go, this is freaking astounding. This is just this moment. You know, without having to do anything is already. Pretty cool. You know, it's almost I hesitate to use the word perfection.

There's a sense of perfection, innate perfection, here and now, without needing to do anything to make it so, because it's already so. So for me, that is just profoundly you know, so I, yeah, I don't I don't really you know, I'm going to live until I die and that's it, you know, I don't really have any.

No, I don't have any profound answers to that question.

Leafbox: No, it's just an interesting question. Yeah, some Buddhists become more agnostic and some become more spiritual. It's a really different, each person's an individual path. My, my last question is, do you think you know how you describe the perfection or I use the word perfection, but the bliss and the wonder of the present moment, do you ever find Buddhism to be escapist?

And one of the critiques of Buddhism that it's an escapist philosophy and it ignores suffering. Maybe this is superficial reading of it, but

Tom: yeah, we'll see the thing is that every single Buddhist thing that I've done I've always chosen ones that are like really hard and really challenging and they're not escapes at all They were like if anything you're thinking, okay, well You're in a frying pan of life, and you want to jump up, but you're jumping into the fire.

It's like It's not an escape at all I'm sure there's some things, you know, like, you know, there's some traditions where you know all you have to do have faith in say Now, I don't want to say, this may be very profound for some people and I don't want to judge that, but for some people it's just having faith in Amitabha Buddha, for example.

Leafbox: That's my favorite buddhism.

Tom: Yeah. So, so, so I feel, no wait I haven't got to the good part yet. I went through a period of time where I just have such profound appreciation for the person of Shinran. I don't know if you're familiar with Shinran. He's like a, and what he did was like so incredible because he made the highest realm of Mahayana non duality relevant to peasants in Japan, you know, unbeknownst to them, right?

You know, because like, if you study like, you know, Mahayana Buddhism and look at the shin path, for example, it's all about non duality, really. It's like, you know, you just, you know, at one point, what you're doing is you're having faith. in an external Buddha, but at one point you're actually, well, this is my reading, is you're actually noticing that there's no difference between, you know, who, like the deluded person I take myself to be and my own inherent Buddha nature as represented by, you know, Amitabha Buddha.

So, So that, so the path is having faith in that, but you have faith in an external Buddha. It's not really a faith in an external Buddha. You're having a faith in your own internal Buddha nature, which to me was a very profound. So what I'm trying to say is that that for me, that's what I consider ultimate my own sense of the ultimate is the non duality between the deluded person that I take myself to be and my own inherent Buddha nature, not only myself, but yours and the whole, and even plants, like Dogen Zenji, the great 12th century Japanese Zen would talk about the, you know, the rocks and streams have, you know, Buddha nature.

So this, there's this sense of this non duality. So that's what I was referring to earlier when you asked me, you know, what's my, like, ultimate. It's more about this non dual nature of, you know, of, you know, the separate person that I, you know, I convinced myself I am, and noticing the fallacy of that, noticing that, the highest ideal of Amitabha Buddha is available to me right here and right now, simply by invoking the Buddha field of Amitabha Buddha.

So I have profound respect for that. But what I'm trying to say is that that's based on non duality. And a lot of people who practice, in my opinion, I know, people who practice the shin path are sort of like thinking about actually more like duality, you know, you know, so for me, you know, I actually got to study with what's his name?

He just died a few years ago. Anyway he told me that that Amitabha Buddha is like, Like Santa Claus, he meant that he says, Tom, this is not, this is Mahayana Buddhism. It's non duality. It's not about Amitabha Buddha somewhere else. It's about Amitabha Buddha as our own Buddha nature.

And I went, okay.

So anyway, so to answer your question, my own thing about spirituality right now is taking things like the Pure Land Path and noticing the non dual nature of that, and to me, like, non dual nature means I don't really have to go outside of my own personal experience to have profound experiences, because it's already profound right now, right here, right now, it's already done, like, we've already crossed the finish line, there's nothing, something that we think we need to do is extra.

That's all I was trying.

Leafbox: So Tom very appreciative of all your wisdom and practice, and how can people find you? What should, how do they connect with Aloha Sangha?

Tom: Yeah. Aloha sangha.com. . Aloha is A-L-O-H-A and Sangha, S-A-N-G-H-A, Aloha sangha.com.

Leafbox: Anything else Tom, you wanna share today or

Tom: No no. Thank you so much.